Last month, I drove back home from France (pics), 1000km in total. 1.5 hours before I reached my destination, I got in the shittiest traffic jam. The horrendous city of Liege swallowed me for a full hour. My phone was broken and got lost on one-way streets. I’ve never been this road-raged.

Table of Contents

The 850km before this went by smoothly. Yet, that traffic jam stood out to me as the entire experience of the trip back home.

Similarly, on the first day at my office after the holidays, the elevators were not working. Being on the 13th floor, I experienced some friction here. On all other days of the year, I didn’t notice the elevator working.

We are more likely to experience friction than to experience the absence of it. And precisely this is what makes for great ingredients to understand how to reach problem-solution fit.

Designing for fit

Everything humankind makes is designed. Especially solutions. We design solutions to function in a certain context. A car designed for dealing with the loose sand and hills of the Sahara looks different than a car designed for a smooth asphalt F1 race track.

Putting the Sahara truck on the race track could work but it will not be a record time. Vice versa, the F1 car would probably bury itself in the sand.

You could argue that the Sahara truck fits better to the F1 tack than the other way around, yet that depends on how you assess fit. A truck will never win that race, something the F1 car has been designed for.

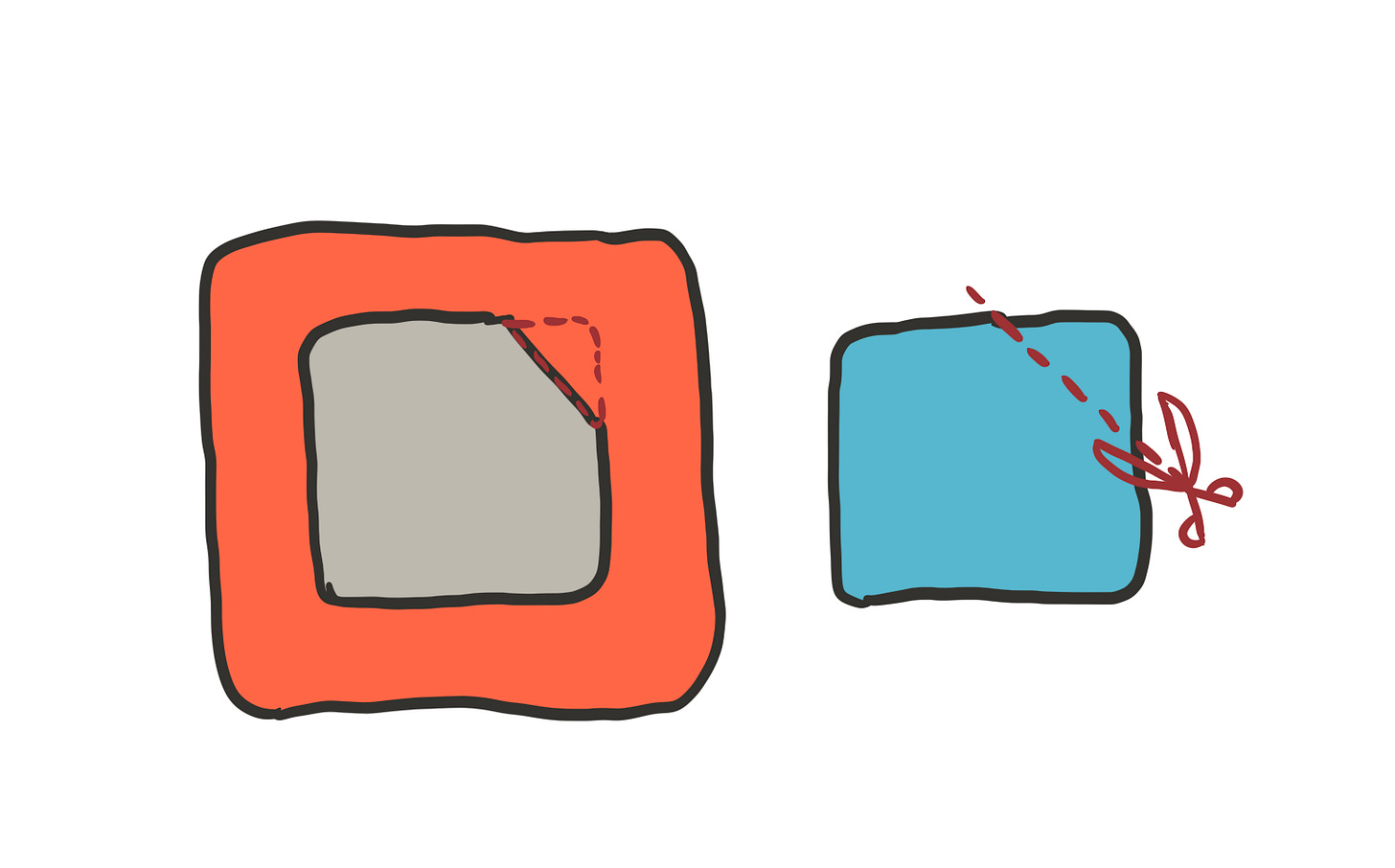

Decreasing misfit to increase fit

Designers optimise the fit between the designed object and its context. How? Design scholar Cristopher Alexander writes about this in his book ‘Notes on the synthesis of form’ (1964).

He argues that we don’t design to increase fit. We design to decrease misfit.

Alexander notes that we are bad at seeing good fit and also at envisioning what makes good fit. We can’t design what we can’t easily envision. Therefore, he argues, designers rarely directly increase the fit.

Instead, designers decrease the misfit. As with my traffic jam or elevator example, we tend to notice the misfit. As humans, we address the misfit to improve the fit.

This book gave me a new point of view I thoroughly enjoyed. What does this lead to? Can’t we directly contribute to fit and solely contribute to decreasing misfit? Let’s grab a practical example.

Fit is holistic

A startup I mentored had a subscription service whose price was too high. They concluded this misfit was due to low sales numbers. They lowered the price to decrease the misfit. By decreasing the misfit, they improved the overall fit, and they assessed, as sales numbers went up.

Two things are important here. First, the assessment of fit is subjective. Fit is measured in relation to the function or intention of the designed object. The F1-car fits well with the track, but maybe not so well with the ecosystem emitting certain gasses.

Secondly, it gets flakey: Did this startup team address the fit directly or indirectly? You could make an argument that they directly improved the fit by lowering the price.

I don’t think that is the most interesting point. My most important take here is the starting point: the misfit. However, addressing one misfit can lead to another.

Because this startup lowered the price by that much that they were not profitable anymore. While they decreased the misfit between their proposition and their customer, they increased the misfit with their own needs of income.

That’s why doing a startup is a holistic design activity. It’s complex: the parts and the whole interrelate in many different ways.

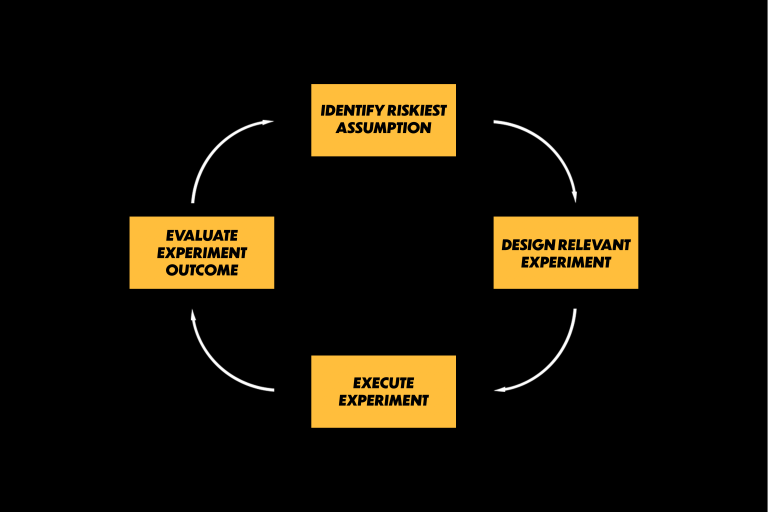

How does this relate to reaching problem-solution fit?

At the start, you have some signals of problem-solution fit. Increasing problem-solution fit requires a thorough understanding of the problem.

That thorough understanding of the problem acts as a stencil. You can cut away all the stuff that isn’t needed. And trust me, initial versions of solutions often have a lot of non-crucial stuff.

Adding features is a risky strategy for increasing fit. If there already are parts of the solution that do not fit well with the user, more features will likely not fix that problem.

If you want to reach problem-solution fit, try to see it as a challenge of reducing misfit between the solution and the problem.

Focus only on what fits well is a red flag, Marty Cagan, writer of product book Inspired tells us:

“They test their prototypes. And when they get enough users saying how much they like it, they build it. And I’m like, “No, that’s not why we do user research.”

[..]

We are not just trying to find out if they like it. In fact, it’s just the opposite. When we’re doing user research, we’re finding all the reasons they don’t like it. In fact, that’s an Elon Musk quote is when you do user a research, you should be focused on finding all the reasons they won’t use your product.” – Full Episode

Don’t wait for perfect fit

Perfect fit doesn’t exist. There are always some gaps. For your first users, your early adopters, these gaps can be sizeable. For the mass, these gaps need reducing. What is the level of fit that’s good enough for your current market segment you are trying to tackle?